20 years ago, none might’ve ever thought of sharing any personal assets with strangers. Sharing access to rooms, tractors or cars with strangers was weirdly intrusive. However, now companies like Uber, Airbnb, Zoomcar, Furlenco, etc. have made temporary “access” to such assets seamless and safer.

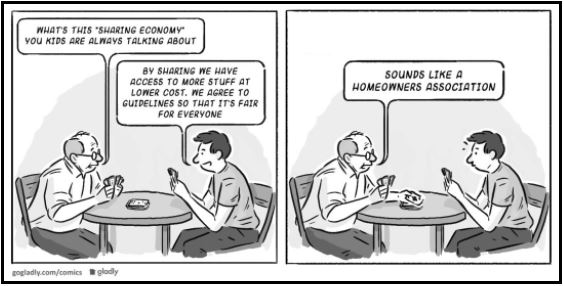

Sharing is not new to us. Today, the moral of sharing has undergone a technology driven transformation, creating disruptions in a number of traditionally established industries across the globe. A collaborative economy, also known as “sharing economy” and “access economy”, provides a peer-to-peer (P2P) service with the help of a web-based middleman. It offers a decentralized platform whereby two consumers interact directly with each other, without a third-party intermediary for their wants and needs. Resources are shared with a much larger pool of people (complete strangers) who are verified via their online presence, ratings and reviews. It consists of access-based services which involves giving, swapping, borrowing, trading and sharing with customers, access to underutilised assets on a temporary basis in return for an access payment. It offers a certain degree of freedom in using the product while legal ownership remains still with the owner of the product.

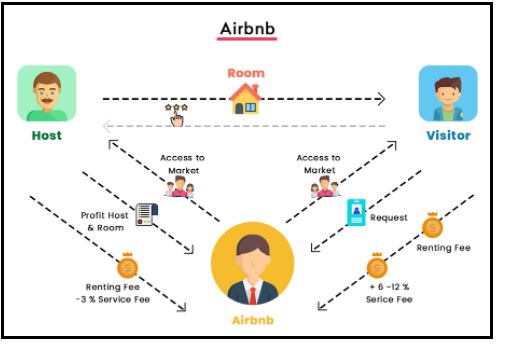

Now let’s take a look at the business model of Airbnb which has exploited the ‘peer-to-peer services model’ to become the behemoth unicorn it is. Two schoolmates, Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia, based out of San Francisco rented their living room with a makeshift bed and breakfast to cover their exorbitant rental charges. During the financial crisis of 2008, the two, along with Nathan Blecharczyk, developed a website for short-term rentals which is now known as ‘Airbnb’. It provides a platform for listing properties for ‘sharing’ depending on the demand and supply of rooms. In December 2020, the short-term rental giant was valued at around $86.5 billion which was more than the combined market capitalization of the top three hotel chains globally. Hilton Worldwide Holdings, Marriott International, and Intercontinental Hotels Group together were valued at $84.1 billion. (Sonnemaker, 2020)

Service fees from bookings which are levied on both guests and hosts is the key source of Airbnb’s revenue. When a reservation is booked, the guests are called to pay a requisite non-refundable service fee until and unless the host cancels or retracts the listing. The service fee is dependent on the size of the reservation as well as the type of listing which is generally under 14.2%. Nevertheless, it must be noted that a more expensive reservation leads to lower service fees so that families or groups with larger reservations can save money for other travel expenses. If the reservation is swapped, Airbnb adjusts the service fee to accommodate customers. And, hosts are charged a 3% fee for every completed booking to cover the processing charges for processing of guest payments. (Nath, 2020)

The sharing economy is not confined to just ride-sharing apps (eg. Uber) and room rentals (eg. Airbnb). Segments of shared economy includes co-working (eg. WeWork), co-living (eg. OYO living) and furniture rental (eg. Furlenco). Did you know that an app which offers a platform for renting agricultural machinery was based in India? In 2016, Mahindra and Mahindra Ltd (M&M) established Trringo, a sharing platform that allows farmers to rent agricultural machinery. Here, farmers book agricultural equipment through their smartphones or Trringo call centres. (Bhattacharya et al., 2017) These examples indicate the potential of the shared economy to ripple through the economy.

Sharing economy has been in the limelight as it is more cost-effective. Convenience, variety, reduced transaction costs, quality and transparency has attracted customers. It is an eco-friendly option as it reduces pollution and waste. (Airbnb, n.d.)

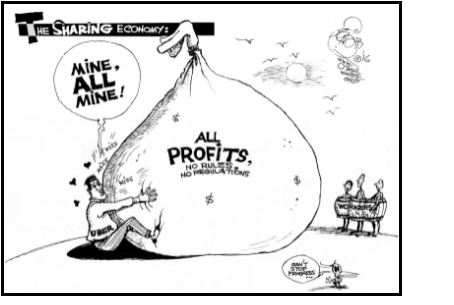

While it may seem that the sharing economy is a win-win for all the three entities. There are a few points that we may overlook and they are as follows:

- Digital divide: Not everyone has access to the internet. It’s meant for the haves and not the ‘havenots’.

- Security of job: The companies could increase their fees, depending on market situations. Workers are not guaranteed health insurance, paid sick leaves, vacations or any other normal benefits that workers of the traditional business may have.

- Extra charges: The hosts have to incur maintenance charges and pay taxes.

- No government regulation: Hotels have regular safety inspections while these firms do not and they exploit labour laws and deregulation. Denmark became the first country to enable Airbnb hosts to report income directly to tax authorities in 2018. (Rinne, 2019)

So, is collaborative consumption here to stay?

Traditional patterns of ownership and consumer behaviour have seemingly been turned upside down. The sharing economy has threatened many incumbent traditional businesses. 20 years ago, ownership used to act as an identity for an individual but now we gladly part away with our underutilized assets to gain secondary income. We see an increasing trend of detachment from possessions. There is a shift in attitudes to what ownership really stands for and relationship between ownership and identity. Millennials contribute maximum to the sharing economy model. (Maycotte, 2015)

Let’s take a look at China where peer-to-peer rental of goods boomed like no other country in the world. The Chinese government had named the sharing economy a national priority. In 2016, the Chinese sharing economy reportedly jumped more than 75% in size and accounted for over 500 billion dollars in transactions. The most successful venture using the sharing economy in China is that of China’s version of Uber. DiDi completed 1.4 billion rides whereas Uber took 6 years to reach 1 billion Chinese sharing economy went to the extent of sharing basketballs, power banks and beds called “napping pods” (which was later discontinued). Experts say that in China, there’s a different relationship between individual ownership and shared access to things i.e. people needing to own products and services outright versus wanting the benefit of them. By 2025, the sharing economy is expected to be 20% of China’s GDP. (Pennington, 2017)

Now, let’s take a look at three likelihoods of the sharing economy in the future:

- Near monopoly: Data is the glue behind the sharing economy. AI will revolutionize our lives including online interactions. Learning algorithms could help minimise online frauds, promote trust by increasing transparency. Massive networks could emerge around one platform provider, the bigger the connectivity and network, the more it grows. The datasets of these networks can be used to leverage AI for diversification from housing to insurance to mobility. Firms of the sharing economy will exhibit oligopolistic trends where the market shares will be concentrated in the hands of a few players. It would be difficult to have a monopoly since the cost for customers to switch between sharing economy services is quite low.

- Near-monopoly within a social bubble: This has a very close resemblance to near monopoly. Here, the difference would be that companies act within a certain social bubble. These bubbles will create their own networks and occupy niche markets that are not covered by giant players. These companies have the best data and knowledge catering to very specific needs.

- Decentralised and Regulated market: Here, we may see autonomous markets with blurry boundaries where most customers will become micro entrepreneurs. Since customers are connected and they may trade with each other, disintermediation is a possibility. The sharing economy would be regulated by the government. (Fehrer et al., 2018, 859-882) Role of regulations in the sharing economy would become lower barriers to entry for companies, which would raise competition for incumbents. Sharing data and algorithms with the government is the one way that sharing economy companies would build confidence and trust with regulators.

According to a study conducted by Brookings India in 2017, the sharing economy is estimated to grow from $14 billion in 2014 to $335 billion by 2025 with increased internet penetration and AI. This estimate is based on the rapid growth of Uber and Airbnb. (Brookings India et al., n.d.,)

Every chat on WhatsApp, every picture of a meal uploaded on Instagram, every new social media platform, we see that the internet facilitates ‘sharing’ and helps to add value. Every transaction and interaction involves ‘sharing’. All of this was possible only due to innovation to increase efficiency and for optimum utilisation of resources. We see that entrepreneurial agility is the currency of the 21st century. It’s important to ensure that in the race to economic growth, we build a sustainable sharing economy that depends on two aspects: attitudinal changes and building trust.

Writer: Merlin Sebastian, TYBA

Bibliography

Airbnb. (n.d.). New Study Reveals A Greener Way to Travel: Airbnb Community Shows Environmental Benefits of Home Sharing. Airbnb. https://www.airbnb.co.in/press/news/new-study-reveals-a-greener-way-to-travel-airbnb-community-shows-environmental-benefits-of-home-sharing?locale=en

Bhattacharya, r., Augustinraj, R., & Wallenstein, J. (2017, November 22). Sharing Economy: creating opportunities in the digital era. Livemint. https://www.livemint.com/Opinion/9jv8S19bns1bBGPutDzpaO/Sharing-economy-creating-opportunities-in-the-digital-era.html

Brookings India, Ravi, S., & Yaraghi, N. (n.d.). The Current and Future State of the Sharing Economy. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/sharingeconomy_032017final.pdf

Fehrer, J. A., Benoit, S., Aksoy, L., Baker, T. L., Bell, S. J., Brodie, R. J., & Marimuthu, M. (2018, November 8). Future scenarios of the collaborative economy: Centrally orchestrated, social bubbles or decentralized autonomous? Journal of Service Management, 29(5), 859-882. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-04-2018-0118

Maycotte, H. O. (2015, May 05). Millennials Are Driving The Sharing Economy — And So Is Big Data. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/homaycotte/2015/05/05/millennials-are-driving-the-sharing-economy-and-so-is-big-data/?sh=731516498cb5

Nath, T. (2020, December 10). How Airbnb Makes Money. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/112414/how-airbnb-makes-money.asp

Pennington, J. (2017, June). The numbers that make China the world’s largest sharing economy. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/06/china-sharing-economy-in-numbers/

Rinne, A. (2019, January). 4 big trends for the sharing economy in 2019. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/sharing-economy/

Sonnemaker, T. (2020, December 11). Airbnb is worth more than 3 largest hotel chains combined after its stock popped 143% on its first day of trading.